5. Repetitions¶

On many occasions programs have to repeat certain calculations or actions over and over. That’s in fact why computers were invented. Unlike persons, programs don’t get bored or fatigued. We will deal with two kind of repetions in this reader:

repetitions that continue as long as a certain condition is met

repetitions over a collection of numbers, elements of a list and such. Both are constantly applied in real-world programs.

5.1. While (conditional repetitions)¶

As a first example where repetitions are useful, consider the example of calculations. The following code calculates sales tax (dutch: “btw”):

tax_rate = 0.21

amount_before = float(input('Amount before tax: '))

sales_tax = tax_rate * amount_before

print('Sales tax: ', sales_tax)

An example run could be:

Amount before tax: 200.00

Sales tax: 42.0

It would be tedious to restart the program over and over again if we want to do multiple calculations. The standard way to handle this type of situation is with a so-called while loop. Figure 5.1 shows the principle in a flowchart. As you can see, after every repetition the condition (asking: another?) is re-evaluated, to see if another repetition is required. Note the loop in the flow-chart, this is while repetitions are often called loops in programming.

Fig. 5.1. Flowchart of repeating a calculation. Left: the specific sales tax example. Right: the general pattern of actions/decisions.¶

In Python code the lines above would be placed in a while statement:

another_calculation = input('Do you want a calculation? ')

while another_calculation == 'yes': # repeat as long as it is 'yes'

tax_rate = 0.21 # sales tax is 21 percent

amount_before = float(input('Amount before tax: '))

sales_tax = tax_rate * amount_before

print('Sales tax: ', sales_tax)

print()

another_calculation = input('Another calculation? ')

print('I love calculations! See you next time.')

A sample run with the while loop could give this output:

Do you want a calculation? yes

Amount before tax: 200

Sales tax: 42.0

Another calculation? yes

Amount before tax: 80

Sales tax: 16.8

Another calculation? no

I love calculations! See you next time.

While (as long as) the answer to ‘Another calculation?’ is ‘yes’ the program will do one more. While needs a condition to decide to continue or not, just like if. More on conditions in general in the chapter on decisions.

Two things are worth noting. First, the statements that are repeated need to be in a block. This is the same as with the if statements treated earlier.

Second, it could be that no calculations are performed (i.e. zero repetitions). If condition another_calculation == ‘yes’ is False at the start the calculations will not be performed even once, as this sample run shows:

Do you want a calculation? no

I love calculations! See you next time.

repeating a number of times

Let’s look at another important example: repeating a (block) statement for a certain number of times. Suppose we want turtle to draw an octagon (regular 8 sided figure). The naive way of programming would be this:

import turtle

turtle.forward(50) # length of the side is 50 pixels

turtle.left(45) # an octagon needs turns of 45 degrees

turtle.forward(50) # length of the side is 50 pixels

turtle.left(45) # an octagon needs turns of 45 degrees

turtle.forward(50) # length of the side is 50 pixels

turtle.left(45) # an octagon needs turns of 45 degrees

turtle.forward(50) # length of the side is 50 pixels

turtle.left(45) # an octagon needs turns of 45 degrees

turtle.forward(50) # length of the side is 50 pixels

turtle.left(45) # an octagon needs turns of 45 degrees

turtle.forward(50) # length of the side is 50 pixels

turtle.left(45) # an octagon needs turns of 45 degrees

turtle.forward(50) # length of the side is 50 pixels

turtle.left(45) # an octagon needs turns of 45 degrees

turtle.forward(50) # length of the side is 50 pixels

turtle.left(45) # an octagon needs turns of 45 degrees

While this code would certainly produce an octagon (try it out), it is clear that this way of programming is clumsy. It has two major drawbacks: (1) it is very easy to make programming mistakes through copy-and-paste (2) more importantly: the code is inflexible, i.e. only 8 sides could be drawn with this code.

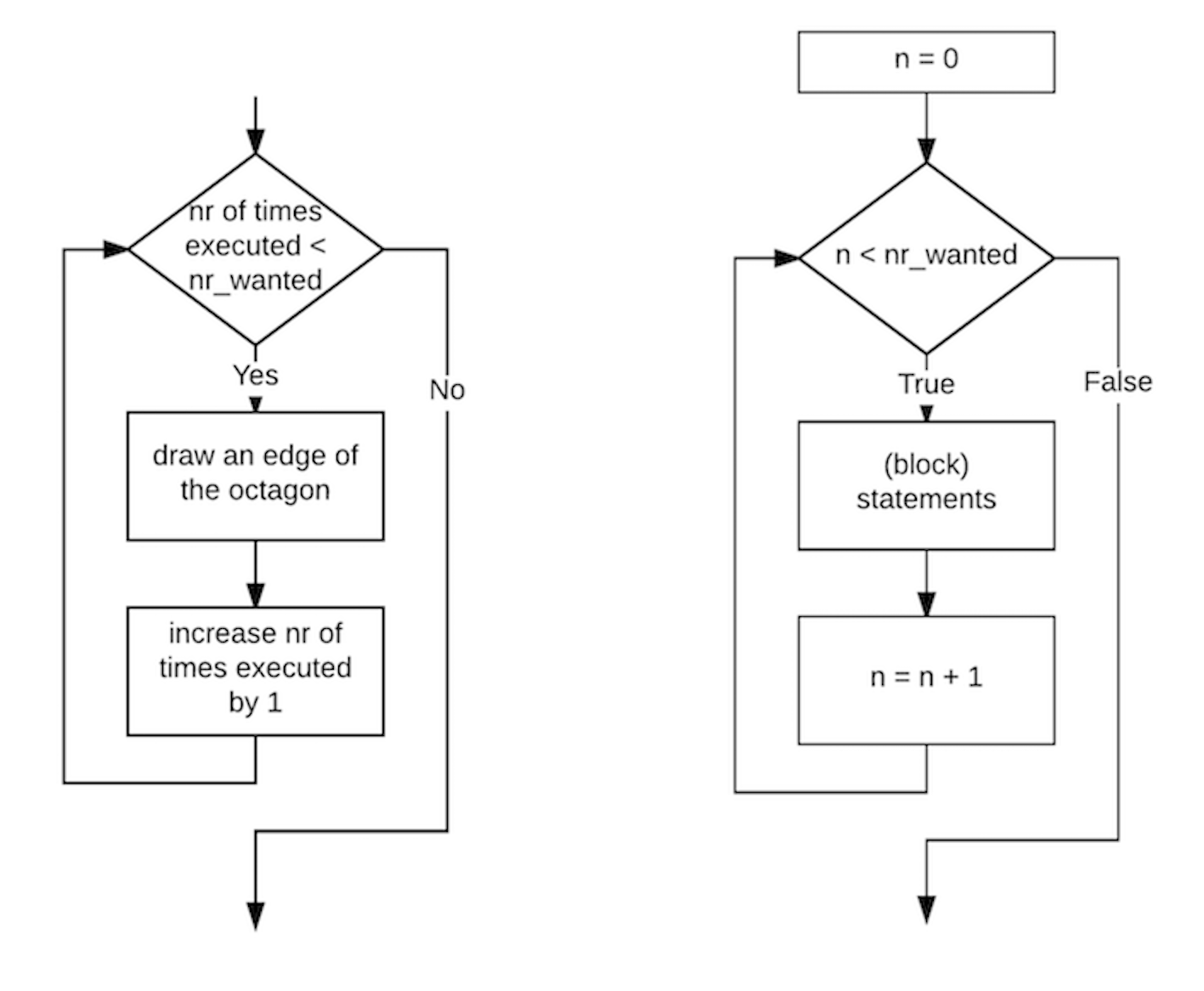

The standard way to handle this is by introducing a counter variable (usually called n or i) that keeps track of the number of executed repetitions and a condition that compares n with the desired number of repetitions. Figure 5.2 shows the flowchart of the principle of counting the number of times code has been executed in a counter variable.

Fig. 5.2. Flowchart of the turtle while example. Left: The concrete case of the turtle drawing an octagon. Right: Translation of the general counting loop to (Python) variables and a condition.¶

In Python the code would be:

import turtle

nr_wanted = 8

n = 0 # n is the counter (a.k.a. iterator)

while n < nr_wanted: # nr_wanted is the number of repetitions

turtle.forward(50)

turtle.left(45)

n = n + 1

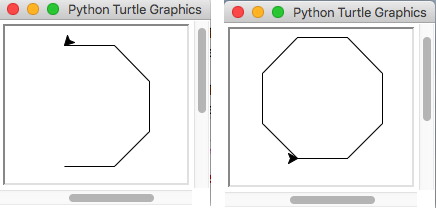

This code is much more compact and flexible than the code above. Variable nr_wanted could be easily set to another number and it would still give the correct number of repetitions. Figure 5.3 shows sample output for nr_wanted set to 5 and 8.

The start value of n = 0 for the counter may seem odd at first glance. It is actually a handy choice. This way the counter variable n always contains the number of repetitions that have already been done (please verify this by stepping through the code). Therefore, in almost all programming languages counting is done from 0 up (and not from 1 like in the real world).

Note that - like in the sales_tax example - 0 repetitions is still possible. If nr_wanted is assigned a value of 0, then the condition n < nr_wanted is False (0 < 0 == False) and the block_statement is not executed at all. Please verify with the code above that this is true.

Fig. 5.3. Sample output of the turtle example. Left: nr_wanted = 5. Right: nr_wanted = 8.¶

5.2. For (counted repetitions)¶

5.2.1. iterating over a range of numbers¶

The while statement can be used to achieve any kind of repetition in a program, because it is so versatile. If the number of repetitions is known beforehand there is a simpler statement that will do the same job: for. Let’s look at a simple example. To repeat a statement 5 times we can use this construction:

for n in range(5):

print("n is", n)

Instead of using a while ststement with a counter variable, we call the range() function passing 5 as an input parameter. The range() function will generate an sequence of integers in the range of 0 up to (but not including) 5.

The range function can produce different variants of number sequences as shown in this code example:

for n in range(3, 6):

print("n is", n)

which produces:

n is 3

n is 4

n is 5

In this code the increment in the number is by 2 instead of 1:

for n in range(5, 11, 2):

print("n is", n)

which produces:

n is 5

n is 7

n is 9

To conclude the range() examples, here is one to show that a negative step can be used to produce a decreasing sequence of numbers:

for n in range(9, 3, -2):

print("n is", n)

with output:

n is 9

n is 7

n is 5

To summarize, there are 3 variants of range:

variant |

interval |

increment |

|---|---|---|

range(n) |

\(0 \leqslant index < n\) |

1 |

range(n1, n2) |

\(n1 \leqslant index < n2\) |

1 |

range(n1, n2, n3) |

\(n1 \leqslant index < n2\) |

n3 |

5.2.2. iterating over the items of a list¶

Let’s look at another common use of for: iteration over all items in a list.

emotions = ['happy', 'sad', 'angry', 'excited']

# output all items from list emotions

for item in emotions:

print(item)

The code fragment above will produce this output:

happy

sad

angry

excited

If we compare this code with a while loop that does exactly the same:

emotions = ['happy', 'sad', 'angry', 'excited']

# output all items from list emotions

n = 0

while n < len(emotions):

print(emotions[n])

n = n + 1

we see that the for statement does not have the administrative overhead (variable n) of counting and incrementing the index. Thus, in cases like this, the for statement is preferred over the while statement.

5.2.3. simultaneous iteration over list items and indeces¶

There are many times when you need both the item in a list and it’s index at the same time. One simple way of handling this situation is with a for-in-range. As a simple example, let’s assume the colors of the rainbow are inside list rainbow:

rainbow = ['red', 'orange', 'yellow', 'green', 'blue', 'indigo', 'violet']

and we would like to display both the index and the contents of each item.

The natural thing to use would be a for loop:

for color in rainbow:

print(color)

but there is no information about the index in a for statement of this kind.

We can solve this problem by using len (rainbow) in combination with a range :

for i in range( len(rainbow) ):

print(i+1, rainbow[i])

which produces the desired output:

1 red

2 orange

3 yellow

4 green

5 blue

6 indigo

7 violet

Please note that i + 1 was only used to convert to the “normal” way of counting from 1 instead of 0.

This pattern of for index in range ( len (list)) can be used in all cases where information about both index and item is required in the iteration. For the interested reader: a more advanced way of dealing with simultaneous iteration is the use of the built-in enumerate(…) function, which is beyond the scope of this course.

© Copyright 2022, dr. P. Lambooij

last updated: Sep 02, 2022