7. Objects and Classes¶

7.1. Introduction¶

With the material in the preceding chapters, you are able to solve many programming problems by using selections, loops, and functions. However, these techniques are not sufficient for developing more sofisticated software, like a graphical user interface (GUI), or a large-scale software system, like a travel planner (‘NS reisplanner’) that consists of both a program running on your PC and planning programs running on some server. To handle this type of complexity, so-called Object Oriented programming techniques are needed. In this chapter the basic concepts of objects and classes (the way to define objects) are introduced, illustrated with examples of how you program them in Python.

In OO programming, an object typically represents an entity in the real world. Examples are a Student, a Desk, a Circle and a Button. Also “cognitive entities” like a StudentLoan, a Country or a University can all be treated as objects with certain properties attached to them.

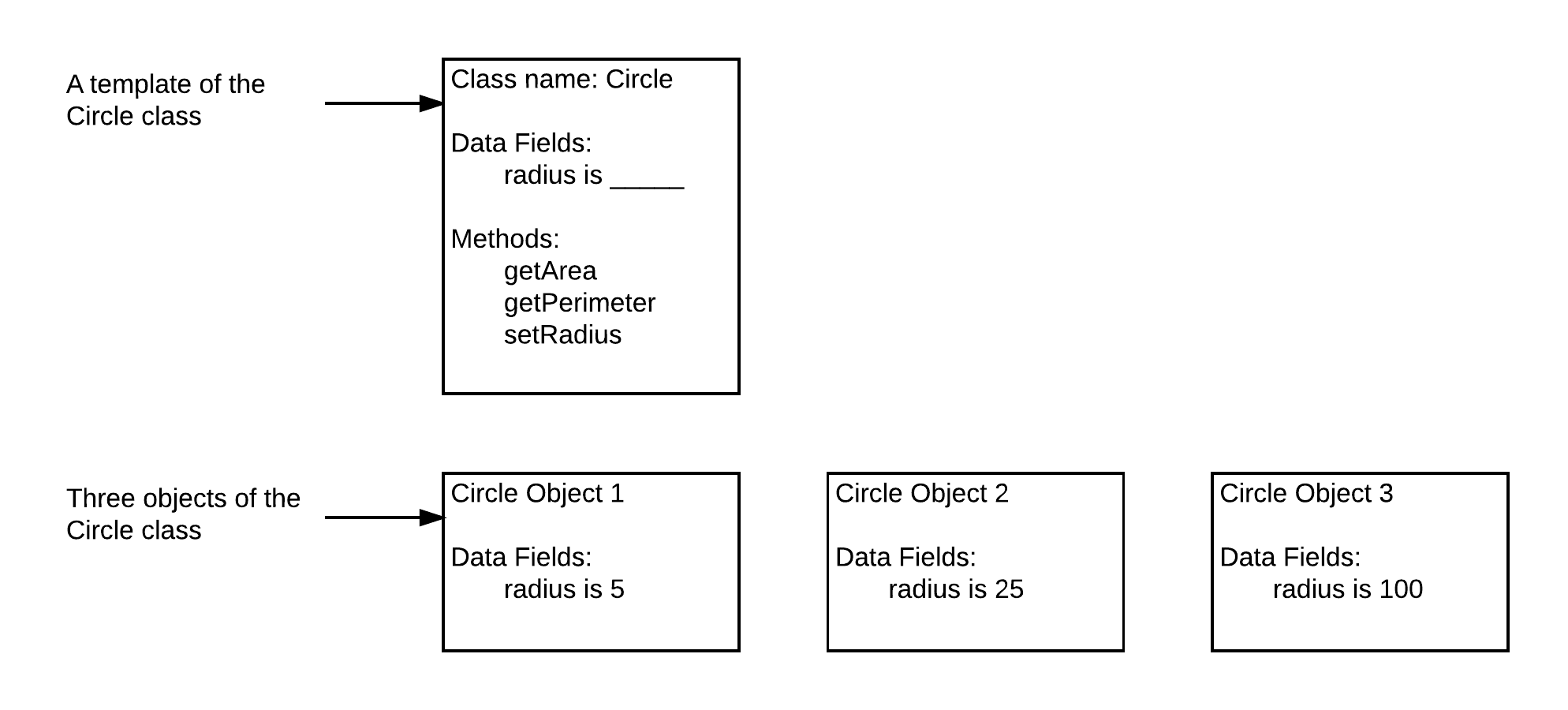

Objects of the same kind are defined once in a so-called class. The relationship between classes and objects is analogous to that between an apple pie recipe and an apple pie. Once you have a class (recipe) you can make as many objects (apple pies) as you want. Figure 7.1 shows a common way of visualising classes and objects, using the concept of a circle, with a single property ‘radius’. All objects created from class Circle have in common that they have a property radius, but each object has it’s individual value of this property. The properties are often called atttibute.

Fig. 7.1. Class Circle with three Circle objects.¶

7.2. Defining and using a class¶

A Python class uses variables to store attributes and defines methods to perform actions. A class is a contract—also sometimes called a template or blueprint—that defines what an object’s attributes and methods will be.

As a simple first example, consider the code below:

# program circle.py

import math

class Circle:

# Construct a circle object

def __init__(self, radius): # initializer

self.radius = radius # property or attribute

def setRadius(self, radius):

self.radius = radius

def getArea(self):

return self.radius * self.radius * math.pi

def getPerimeter(self):

return 2 * self.radius * math.pi

This code defines a simple class called Circle. The class name is preceded by the keyword ‘class’, followed by a block of statements that define all functions of the class. By tradition, class function are referred to as methods.

Once class Circle has been defined, you can objects from the class with a so-called constructor, that has the same name as the class (in this case Circle()).

Here is an example of the use of class Circle:

def main():

# Create a circle with radius

circle1 = Circle(1)

area1 = circle1.getArea()

print("The area of the circle of radius",

circle1.radius , "is", area1)

# Create a circle with radius 5

circle2 = Circle(5)

area2 = circle2.getArea()

print("The area of the circle of radius",

circle2.radius, "is", area2)

# Create a circle with radius 100

circle3 = Circle(100)

area3 = circle3.getArea()

print("The area of the circle of radius",

circle3.radius, "is", area3)

# Modify circle radius

circle2.setRadius(10)

new_radius2 = circle2.getArea()

print("The area of the circle of radius",

circle2.radius, "is", new_radius2)

main()

In the example above, function main() uses the Circle class to create Circle objects circle1, circle2 and circle3 with a radius of 1, 5, and 100 by calling Circle(1), Circle(5) and Circle(100), respectively.

After creation, the program displays the radius and area of circle1, circle2 and circle3. The program then changes the radius of circle2 to 10 with circle2.setRadius(10) and displays its new radius and area:

The area of the circle of radius 1 is 3.141592653589793

The area of the circle of radius 5 is 78.53981633974483

The area of the circle of radius 100 is 31415.926535897932

The area of the circle of radius 10 is 314.1592653589793

Note that the methods of the Circle objects circle1, circle2 and circle3 are called with a ‘.’ This is the so-called ‘dot’ operator. It is used to get access to method ‘getArea()’ of object circle1 etc. For this reason the ‘.’ is sometimes called accessor operator:

# concrete example:

circle2.setRadius(self, 10)

# general way of calling a method:

object_name.method_name(self, parameter1, parameter2, ...)

7.3. The constructor and __init__¶

Every class has one special method called __init__, which defines the starting values of an object upon creation. Note that __init__ always starts and ends with two underscores. In class ‘Circle’, only one attribute radius is created in __init__. In addition, methods ‘getPerimeter()’ and ‘getArea()’ are defined to return the perimeter and area of the circle object. Also, ‘setRadius()’ is defined that allowes changes in radius after the object has been created. More details on the initializer, attributes, and methods will be explained in later sections of this chapter.

All methods, including __init__, have the same first parameter: self. This parameter refers to the object on which the method is called. We will discuss the role of self in more detail in a separate section.

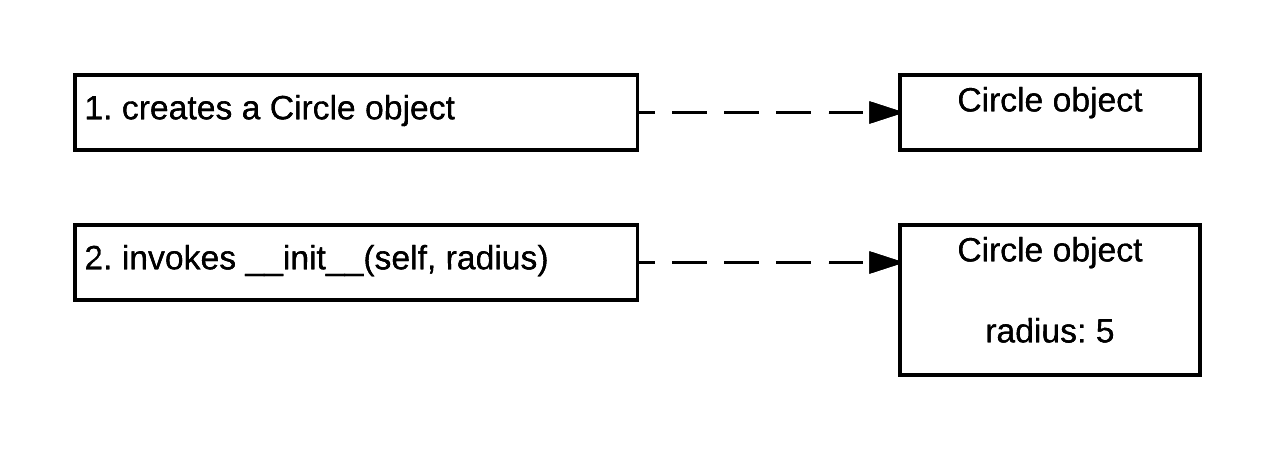

Let us look into the process of creating an object in some more detail. An object is created by calling a so-called constructor. The constructor does two things:

It creates an object of the class.

It calls the __init__ method of the class to initialize the object.

Method __init__, also known as the initializer, is called automatically, when an object is created. Its purpose is to create the attributes of the object and assign initial values to them.

Figure 7.2 depicts the effect of constructing a Circle object using Circle(5). First, a Circle object is created, and then the initializer is called to assign value 5 to radius.

Fig. 7.2. A circle object with radius 5 is constructed by calling the constructor: Circle(5).¶

The syntax for every constructor is:

objectName = ClassName(argument1, argument2, ...)

In the concrete case of the Circle class this is:

circle1 = Circle(5)

The arguments of the constructor match the parameters in the __init__ method but without self. For example, since the __init__ method is defined as __init__(self, radius), you should use Circle(5) to construct a Circle object with radius 5.

7.4. The ‘self’ Parameter¶

As mentioned earlier, the first parameter for each method defined is ‘self’. This parameter is used in the implementation of the method, but it is not used when the method is called. So, why does Python need parameter ‘self’? It has to do with scoping. The scope of an instance variable (e.g. ‘self.name’) is the entire class once it is created.

As an illustration, in the code fragment below, ‘self.’ has been omitted for attributes __width and __height.

1 class Rectangle: # Construct a Rectangle object

2 def __init__(self, width, height): # initializer

3 __width = width # property width

4 __height = height # property height

5

6 def getWidth(self):

7 return __width

8

9 def getHeight(self):

10 return __height

11

12 def getArea(self):

13 area = __width * __height

14 return area

15

16 def main():

17 rectangle1 = Rectangle(3, 4) # Create a 3x4 rectangle

18 rectangle2 = Rectangle(5, 7) # Create a 5x7 rectangle

19

20 width1 = rectangle1.getWidth()

21 print("Width rectangle 1:", width1)

22

23 height2 = rectangle2.getHeight()

24 print("Height rectangle 2:", height2)

25

26 main()

If you run the code above you will get the following error:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/Users/peterlambooij/Documents/rect.py", line 26, in <module>

main()

File "/Users/peterlambooij/Documents/rect.py", line 20, in main

width1 = rectangle1.getWidth()

File "/Users/peterlambooij/Documents/rect.py", line 7, in getWidth

return width

NameError: name 'width' is not defined

Python does not recognise variable ‘width’ because it is a local variable, it’s scope is only function __init__. Self will expand the scope to the entire class. If we add ‘self.’ to ‘width’ and ‘height’ these variables can be also used in the other functions (getWidth, getHeight and getArea). Here is an example:

1 class Rectangle: # Construct a Rectangle object

2 def __init__(self, initial_width, initial_height): # initializer

3 self.width = initial_width # property width

4 self.height = initial_height # property height

5

6 def getWidth(self):

7 return self.width

8

9 def getHeight(self):

10 return self.height

11

12 def getArea(self):

13 area = self.width * self.height

14 return area

15

16 def main():

17 rectangle1 = Rectangle(3, 4) # Create a 3x4 rectangle

18 rectangle2 = Rectangle(5, 7) # Create a 5x7 rectangle

19

20 width1 = rectangle1.getWidth()

21 print("Width rectangle 1:", width1)

22

23 height2 = rectangle2.getHeight()

24 print("Height rectangle 2:", height2)

25

26 main()

Now variables ‘self.width’ and ‘self.height’ are recognised throughout class ‘Rectangle’ and the output will be:

Width rectangle 1: 3

Height rectangle 2: 7

7.5. Private Attributes¶

In Python you can access attributes (a.k.a. properties) via directly from an object using the ‘dot’ operator. For example, the following code, which lets you access the circles radius from my_circle.radius, is valid:

>>> my_circle = Circle(5)

>>> my_circle.radius = 5.4 # Write a instance variable directly

>>> print(my_circle.radius) # Read instance variable directly

5.4

Although legal, direct access of a attribute in an object is NOT a good practice, for two reasons:

First, data may be tampered with through ignorance or simple programming mistakes. For example, the attribute ‘radius’ in the Circle class should always have a value of 0 and higher, but it could be mistakenly set to a negative value, which makes no sense.

Second, suppose you want to modify the Circle class to ensure that the radius is nonnegative after other programs have already used the class. Now you have to change not only the Circle class but also the programs that use it, because the clients may have modified the radius directly (e.g. my_circle.radius = -5).

To prevent direct modifications of attributes, experienced programmers don’t let the client directly access attributes. Instead, they define their attributes as private. This best practice is known as data hiding. In Python, the private attributes are designated by two leading underscores. For instance: ‘self.__radius’ is an indication of a private attribute.

Private attributes should only be accessed from code within a class, but they should not be accessed from code outside the class. To make the value of a attribute accessible to code outside the class, a so-called get method is added to the class return its value. To enable a attribute to be modified, a so-called set method is added to the class to enable assigning a new value to it. Get methods are commonly referred to as a getter (or accessor), and set methods are commonly called setter (or mutator).

By convention a get method has the following header:

def getPropertyName(self):

If the return type is Boolean, the get method is usually named as follows:

def isPropertyName(self):

By convention a set method has this header:

def setPropertyName(self, propertyValue):

As an example of private attributes, the following code shows revised code of the Circle class with field ‘radius’ made private:

# module circle_with_private_radius

class Circle:

# Construct a circle object

def __init__(self, radius):

self.__radius = radius # private radius

def getRadius(self): # getter for radius

return self.__radius

def setRadius(self, new_radius): # setter for radius

if radius > 0:

self.__radius = new_radius

def getArea(self):

return self.__radius * self.__radius * math.pi

Now it is clear from the underscores that the radius property should not be directly accessed from the outside in this new Circle class. Instead you should read or modify it by using the ‘getRadius()’ or ‘setRadius(…)’ methods:

>>> from CircleWithPrivateRadius import Circle

>>> circle = Circle(5)

>>> circle.getRadius()

5

>>> circle.setRadius(8)

>>> circle.getRadius()

8

When to use private attributes or not?

As a general rule, private attributes are definitively needed if you have a class that is intended for other programs to use. This way you prevent data from being tampered with and to make the class easy to maintain, define attributes as private. Private data are not strictly needed if a class is only used internally by your own program, but most professional programmers do it anyway, because it also helps to prevent programming mistakes.

7.6. Storing Classes in Modules¶

The programs you have seen so far in this chapter have the Circle class definition in the same file as the programming statements that use the Circle class. This approach works fine with small programs that use only one or two small classes. As programs use more classes, however, the need to organize those classes becomes greater. Programmers commonly organize their class definitions by storing them in a separate modules for every class definition. Then the modules can be imported into any programs that need to use the classes they contain.

For example, suppose we decide to store the Circle class in a module named circle(.py). Then, when we need to use the Circle class in a program, we can import the Circle class from the circle. This is demonstrated below with the code split over files circle.py and main.py:

# code of circle.py

# module circle_with_private_radius

class Circle:

def __init__(self, radius): # construction a circle object

self.__radius = radius # private radius

def getRadius(self): # getter for radius

return self.__radius

def setRadius(self, new_radius): # setter for radius

if radius > 0:

self.__radius = new_radius

def getArea(self):

return self.__radius * self.__radius * math.pi

The code of module main.py uses the Circle class by an import:

# code of main.py

from circle import Circle

def main():

# Create a circle with radius

circle1 = Circle(1)

area1 = circle1.getArea()

print("The area of the circle of radius",

circle1.radius , "is", area1)

# Create a circle with radius 5

circle2 = Circle(5)

area2 = circle2.getArea()

print("The area of the circle of radius",

circle2.radius, "is", area2)

# Create a circle with radius 100

circle3 = Circle(100)

area3 = circle3.getArea()

print("The area of the circle of radius",

circle3.radius, "is", area3)

# Modify circle radius

circle2.setRadius(10)

new_radius2 = circle2.getArea()

print("The area of the circle of radius",

circle2.radius, "is", new_radius2)

main()

© Copyright 2022, dr. P. Lambooij

last updated: Oct 07, 2022